When Hillary Clinton called for a “Manhattan-like project” to find a way for the government to spy on criminals without undermining the security of everyone else’s communications, the technology world responded with mockery.

“Also we can create magical ponies who burp ice cream while we’re at it,” snarked prominent Silicon Valley investor Marc Andreessen. Clinton’s idea “makes no sense,” added Techdirt’s Mike Masnick, because “backdooring encryption means that everyone is more exposed to everyone, including malicious hackers.”

It’s an argument that’s been echoed by Apple CEO Tim Cook, who is currently waging a legal battle with the FBI over its request to unlock the iPhone of San Bernardino terrorism suspect Syed Rizwan Farook. “You can’t have a backdoor that’s only for the good guys,” Cook said in November.

There’s just one problem: This isn’t actually true, and the fight over Farook’s iPhone proves it. Apple has tacitly admitted that it can modify the software on Farook’s iPhone to give the FBI access without damaging the security of anyone else’s iPhone.

Claiming that secure back doors are technically impossible is politically convenient. It allows big technology companies like Apple to say that they’d love to help law enforcement but don’t know how to do it without also helping criminals and hackers.

But now, faced with a case where Apple clearly can help law enforcement, Cook is in the awkward position of arguing that it shouldn’t be required to.

Apple isn’t actually worried about the privacy of a dead terrorism suspect. Cook is worried about the legal precedent — not only being forced to help crack more iPhones in the future, but conceivably being forced to build other hacking tools as well.

But by taking a hard line in a case where Apple really could help law enforcement in an important terrorism case — and where doing so wouldn’t directly endanger the security of anyone else’s iPhone — Apple risks giving the impression that tech companies’ objections aren’t being made entirely in good faith.

The San Bernardino case shows secure back doors are possible

Technologists aren’t lying when they say secure back doors are impossible. They’re just talking about something much narrower than what the term means to a layperson. Specifically, their claim is that it’s impossible to design encryption algorithms that scramble data in a way that the recipient and the government — but no one else — can read.

That’s been conventional wisdom ever since 1994, when a researcher named Matt Blaze demonstrated that a government-backed proposal for a back-doored encryption chip had fatal security flaws. In the two decades since, technologists have become convinced that this is something close to a general principle: It’s very difficult to design encryption algorithms that are vulnerable to eavesdropping by one party but provably secure against everyone else. The strongest encryption algorithms we know about are all designed to be secure against everyone.

But the fact that we don’t know how to make an encryption algorithm that can be compromised only by law enforcement doesn’t imply that we don’t know how to make a technology product that can be unlocked only by law enforcement. In fact, the iPhone 5C that Apple and the FBI are fighting about this week is a perfect example of such a technology product.

You can read about how the hack the FBI has sought would work in my previous coverage, or this even more detailed technical analysis. But the bottom line is that the technology the FBI is requesting — and that Apple has tacitly conceded it could build if forced to do so — accomplishes what many back door opponents have insisted is impossible.

Without Apple’s help, Farook’s iPhone is secure against all known attacks. With Apple’s help, the FBI will be able to crack the encryption on Farook’s iPhone. And helping the FBI crack Farook’s phone won’t help the FBI or anyone else unlock anyone else’s iPhone.

It appears, however, that more recent iPhones are not vulnerable to the same kind of attack. (Update: Apple has told Techcrunch that newer iPhones are also vulnerable.) If Farook had had an iPhone 6S instead of an iPhone 5C, it’s likely (though only Apple knows for sure) that Apple could have truthfully said it had no way to help the FBI extract the data.

That worries law enforcement officials like FBI Director James Comey, who has called on technology companies to work with the government to ensure that encrypted data can always be unscrambled. Comey hasn’t proposed a specific piece of legislation, but he is effectively calling on Apple to stop producing technology products like the iPhone 6S that cannot be hacked even with Apple’s help.

The strongest case against back doors is repressive regimes overseas

If you have a lot of faith in the US legal system (and you’re not too concerned about the NSA’s creative interpretations of surveillance law), Comey’s demand might seem reasonable. Law enforcement agencies have long had the ability to get copies of almost all types of private communication and data if they first get a warrant. There would be a number of practical problems with legally prohibiting technology products without back doors, but you might wonder why technology companies don’t just voluntarily design their products to comply with lawful warrants.

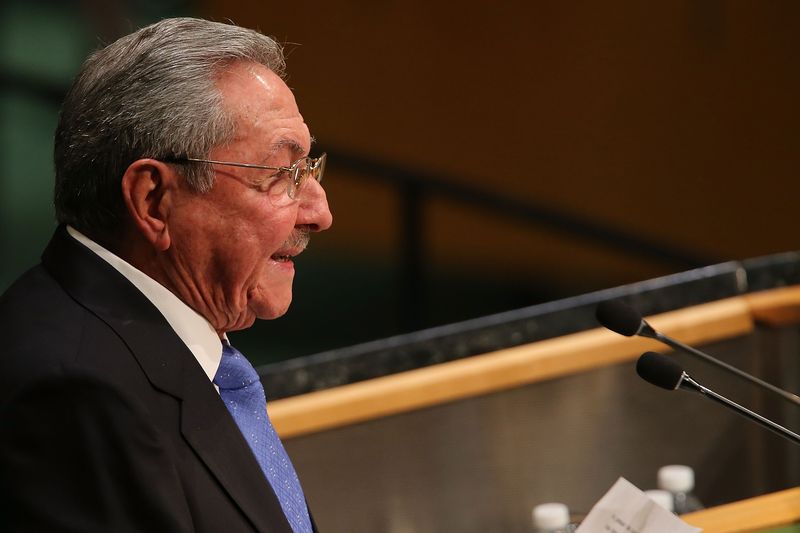

But things look different from a global perspective. Because if you care about human rights, then you should want to make sure that ordinary citizens in authoritarian countries like China, Cuba, and Saudi Arabia also have access to secure encryption.

And if technology companies provided the US government with backdoor access to smartphones — either voluntarily or under legal compulsion — it would be very difficult for them to refuse to extend the same courtesy to other, more authoritarian regimes. In practice, providing access to the US government also means providing access to the Chinese government.

And this is probably Apple’s strongest argument in its current fight with the FBI. If the US courts refuse to grant the FBI’s request, Apple might be able to tell China that it simply doesn’t have the software required to help hack into the iPhone 5C’s of Chinese suspects. But if Apple were to create the software for the FBI, the Chinese government would likely put immense pressure on Apple to extend it the same courtesy.